Artists Find Scientific Support for High-Tech Projects

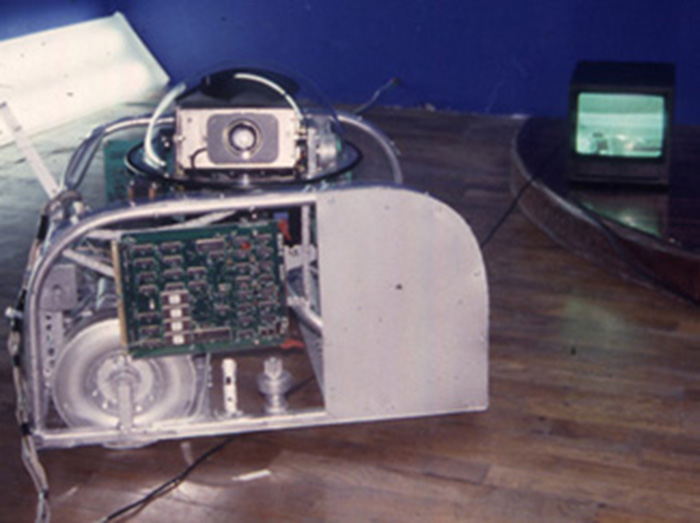

A robot from “The Ship’s Detective,” a 1997 work by Adrianne Wortzel. The artist received a federal grant to buy industrial robots for a new project.

Digital artists who use their creativity to find fresh sources of funds for their work are discovering a new form of support: education and research grants from the scientific community.

The National Science Foundation, for example, has just awarded $50,000 to “Robotic Renaissance,” a theater project by the New York artist Adrianne Wortzel and two Cooper Union engineering professors, Carl Weiman and Chih-Shing Wei.

With a matching grant from the Cooper Union, Wortzel and her colleagues will be able to buy $100,000 worth of commercial and indstrial robots so they can explore how to transform the devices into theatrical performers that respond to the spoken word and other stimuli like sound and light.

The project, which the NSF supported for its educational potential, will result in several dramatic productions. The first will be an Internet event in which online viewers can remotely control the robotic actors, followed by a theatrical staging with a live audience.

In a telephone interview, Wortzel explained why she pursued the NSF grant. “I wanted to up the ante on the kind of robotics I work with, something closer to the state of the art,” she said. For past projects, Wortzel built her robotic actors from scratch.

“I do think you have to be creative” in finding funds, Wortzel said. “How else would I have gotten $100,000 to buy robots?”

The NSF grant would seem to be something of a departure for a federal agency that more typically sponsors science and engineering projects. Charlie Drum, an NSF spokesman, acknowledged that “this one seems kind of unique.”

Not entirely. Although a few digital artists have started to earn museum commissions and foundation grants, those seeking alternative sources of financial support are learning that working on science projects can pay.

As announced in December, the Brooklyn Academy of Music has initiated “Artists in Multimedia,” a two-year partnership with Lucent Technologies in which BAM-selected artists will work on new-media arts projects with scientists from Lucent’s Bell Labs research division.

According to those who applied for the program’s grants, said to be $40,000 each, the initial recipients will be the sound artist Ben Rubin, the film director and playwright John Jesurun, and the digital artist Paul Kaiser, best known for his collaborations with the choreographers Bill T. Jones and Merce Cunningham. All are from New York. BAM plans to officially announce the winners in the next few weeks.

And Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center in California continues to support its PARC Artist In Residence program. This year’s eight participants will work with Xerox researchers to produce artist’s books using digital technology. Most recent projects have had a strong Internet component.

Collaborations between digital artists and high-tech scientists can benefit both sides, and if the technology sector of the economy continues to flourish, “you’re going to see more and more of this,” said Judith A. Jedlicka, president of the Business Committee for the Arts, a nonprofit organization in New York.

“The digital artist is not something the corporation has directly funded” to date, and research grants are a way to do it, said Jedlicka, whose organization acts as a catalyst between business and the arts. At the same time, she said, technology firms, particularly those working with the entertainment industry, have succeeded with the kind of “outside-the-box” thinking that artists can provide.

The concept is not entirely new. In the 1960s, for example, Bell Labs engineers like Billy Kluver began to collaborate with artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. In 1966, Kluver and Rauschenberg founded Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT) to promote interaction between high-tech wizards and the creative community.

“It’s thrilling to be following in the footsteps of the people who were involved in EAT,” said Rubin, who has already begun collaborating with Mark Hansen, a statistician at Bell.

For their Ear to the Ground project, Rubin and Hansen will develop a program that will generate an audio stream reflecting the level of activity at a Web site at any given moment.

Rubin said he expected that the project’s concepts would eventually have broader applications, but he was not concerned that market imperatives would play a role in the project’s evolution. “In order to pursue this, it seems important to put off [considering] the commercial potential for a while,” he said.

Rubin said the four-month residency would give him the time to realize the project, but he also enthused about how the collaboration with Bell scientists would give him “access to fantastic brainpower — wisdom that, as an artist, as someone outside the research community, I’ve only been able to scratch the surface of before.”

Wortzel, too, believes that her project’s success would depend upon her collaborators’ input. “I couldn’t have done this without the engineers,” she said.

But she will do it without involving the hand-built robots from her past projects. “My poor robots are in storage,” she said. “I don’t want to tell them.”

arts@large is published on Thursdays. Click here for a list of links to other columns in the series.

Related Sites

These sites are not part of The New York Times on the Web, and The Times has no control over their content or availability.

- National Science Foundation

- Adrianne Wortzel

- Cooper Union

- Brooklyn Academy of Music

- Lucent Technologies

- Ben Rubin

- Paul Kaiser

- PARC Artist In Residence (PAIR)

- Business Committee for the Arts

- Ear to the Ground

Matthew Mirapaul at mirapaul@nytimes.com welcomes your comments and suggestions.